Battersea Art Centre Exhibition and Performance 1980

Action Space and its Development

Ken Turner

In the Spring of 1968 artists/lecturers at Barnett College’s Environmental Design Course and the Central School of Art and Design, received a call from Joan Littlewood, the avant garde theatre director from the Theatre Royal Stratford East, to engage with her in an ongoing experiment with her idea of ‘instant cities’ in which art, theatre, technology and entertainment would come together as a total public theatre of the arts.

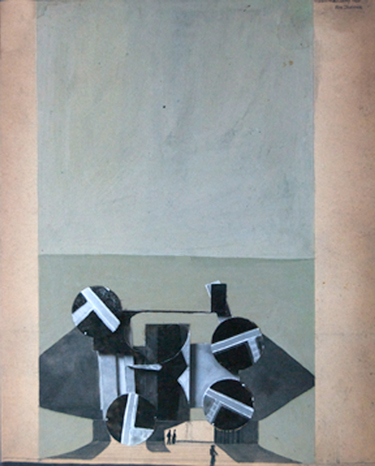

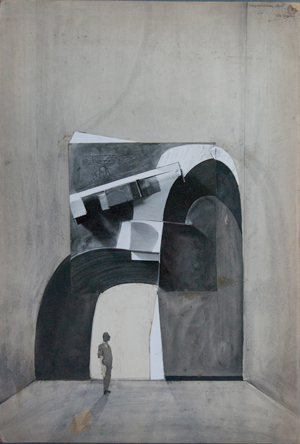

I was then teaching part time at Barnett (1966-1969) and later at the Central 1967-1990), and responded with enthusiasm to Joan’s call with a specific project. As I had been experimenting with performance in the streets of Barnet (photos) and experimenting with the students in wood, metal and plastics, building models for the environment, linked to ideas inspired by the Bauhaus, I was only too ready to make something big in structure, environmental and participatory as an ‘environmental art form’. It was at this time that I stopped painting and exhibiting in the West End Galleries, importantly though, I believed that my exhibitions formed the basis of development in the unfolding ideas of Action Space Structure and the work I now envisioned. Namely the one person shows at the Heals Mansard Gallery, curated by Alannah Coleman, the Australian champion of contemporary art, the Institute of Contemporary Art, supported be Sir Roland Penrose, with the last in The Lords Gallery (1966) in St, Johns Wood called ‘Art as Something Public’ reviewed extensively by Edward Lucy-Smith in Studio International, February 1966, in pursuing an argument in response to my catalogue notes on the ‘private versus public’ nature of art, and how to affect a gallery installation as a proposition to work in the public realm. These exhibitions portrayed the gradual evolvement of ideas and were extremely significant to the later structuring of my practice and action outside the gallery scene. (Photos of sculpture and work from three shows).

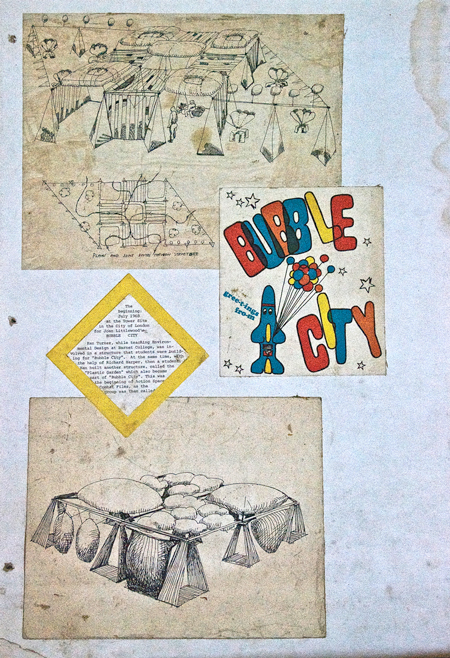

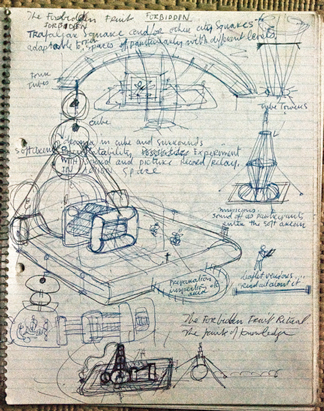

Two years later, after these one person shows and following the Lords show, I worked on an installation as a participatory environment called “The Plastic Garden”, (it was also called Paradise Garden) to be placed alongside other artists and architect’s visions of a new interactive purpose build total environment in the City of London. Placed next to All Hallows-by-the-Tower, this move towards an environmental structure became excitingly real. Situated in sight of the Tower of London, entitled by Joan Littlewood as “Bubble City” in the summer of 1968, it was in parallel to her intentions to build the “Fun Palace” that Cedric Price was in the process of designing. Perhaps it wasn’t incidental that I later in 1977 taught for three years at the Architectural Association, where Cecil taught earlier, leading a Foundation Unit in Visual Education for Architects.

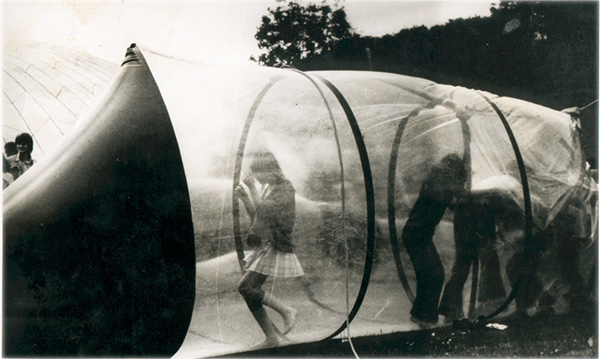

The ‘garden idea’, finally came to be built in my ‘front room studio’ of a family Hampstead flat. The form took shape as an environmental art structure or ‘installation’ ( a word later to be recognised in the art world), assisted by Richard Harper, a student from Barnett. Hinged and slotted wood elements combined with air blown flexible sheet plastics highlighted a practical fruition of ideas that had been long in the incubation period in my mind. A period based on a series of ideas, studies, research into architectural environments and garden landscape design, (see photos of models and sculptures), including implications of post-war development and reconstruction and social and cultural change. Advances brought about by artists and architects seemed at the time extremely relevant. And in this advance, not to forget the rebelling of London art students of Hornsey in search of a new interdisciplinary curriculum degree courses, and the impact of the Paris student revolt of 1968 against outworn institutional ideas. Thirty years later we are still in the throes of discussion on art schools and there purpose, the universities ‘take over’, and subsequently, government restrictions on creativity. Perhaps only now in 2009 we are beginning to realize that creativity from artists is paramount to a thriving culture, providing that is, freedom is kept as a vitalizing force and art’s commercialization as commodity is held at bay: we know the story only too well. However an economist recently declared that artists should sit with economists in order to bring some creativity to the table. If only. Yet I have to say that according to W. B. Yeats “I think it better that in times like these a poets mouth be silent, for truth, we have no gift to set a statesman right”. Not so sure, depends on the times perhaps. And yet both Picasso and Auden are on record as saying that ‘art makes nothing happen’.

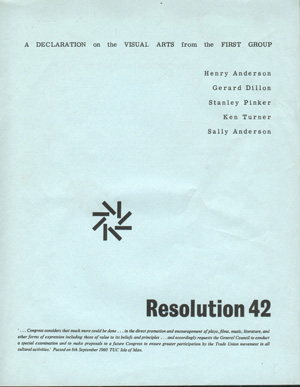

All this was happening when Mary Turner working with young children in a playgroup that our children attended. She was researching the idea of play through theory and practical application with the Play Group Association. Dr. Bowlby’s sister Evelyn-Phelps-Brown was instrumental in our understanding of the value of play. Indeed, we soon realized the seriousness of play and saw how our experiments with air structures in playgroup situations contributed much to our understanding. It seemed a natural course of events then that a “partnership” between us was to arise in order to link the arts with creative play, education and the arts, and to push ahead into what we thought might be an invigorating future. Earlier in 1961 Mary and I had got together an exhibition of the ‘First Group’. The first artists’ led, self-organised group, touring five artists work around twelve Municipal Galleries in the UK. Arnold Wesker, the play-write, was our partner in this venture when we gave a talk on the invitation of William Gear, painter, educator, and curator at the Towner Art Gallery Eastbourne called ‘Two Snarling Heads’ to a conference of Trade Unions, under the banner of ‘Resolution 42’. Later moving into negotiations with the Round House, Chalk Farm under the same banner for a peoples centre.

Our children benefited from our activities from a long way back, though not with the First Group. But were, from the first playgroup events initiated into the experience of large inflatables for rolling and jumping on. As they grew up, Action Space members became, in a sense their larger family. Finally leading them to become performers and innovators themselves: in a sense, a varied, stimulating and creative educational slice of life in the process of growing up. Theodora is now running her own organisation in creative play with Tepee in South Devon, based on ideas of creative play, and Jason is acting and directing whilst teaching at the Jacques La Coque Theatre School in Paris. So something must have rubbed off in their education through art and performance. At one time Jason aged 6 was almost taken to the casualty section of Rotterdam hospital for acting ‘dead’ too convincingly and Theodora aged 8, in acting the part of Alice became a star in the eyes of local children. Performers and musicians who eventually came to work in the group, as it grew in size, spoke about the freedom it gave them from academic rules to find in themselves a new discipline; a sense of relief in that they were ‘allowed’ to experiment and explore territories foreign to their normal practice learnt in academies and universities: three graduates came from a newly set up interdisciplinary course from the Central School of Art and Design, they felt immediately at home and made significant contributions to the group.

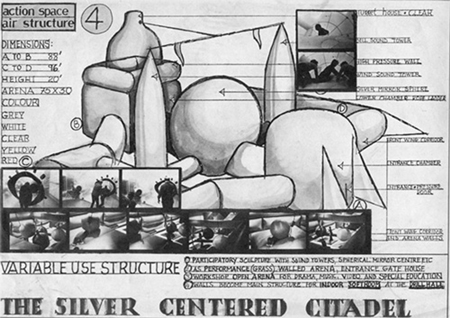

Continuing thus on to a positive and practical exposition interlinked to the idea of education through art, I would like to cite a reference to Herbert Read for his enlightened thoughts in “The Grass Roots of Art” published in 1947; to quote Read because the eventual inflatable designs yet not realized, were to reveal a sense of something of value to its users in their organic nature. That is, inside and outside the air blown membrane, brought a sense of ‘difference to its architectural qualities’: as many people who experienced them have said. “How amazing, the way space is reconstructed is as if by magic, its curving continuous surfaces, organic in nature and breathing a pulse, as if through the membrane, the air movement passing over the body and face, at times fiercely, and then gently. A strangeness too in the space itself, different to our normal feeling of space, a difference that brought people closer together mentally and physically in a new dimensionality ”. In this context, Read again, “The art of a completely mechanized civilization can never, if it is to be art, arise from the purely rational solution of functional problems. The function after all, always relates to human needs. Human needs, in their turn, are always related to the natural environment”. Ideas then current in Peter Cook’s Archigram, Plug in Cities and Bucky Fuller’s domes were part of the forward-looking movement, firmly structural but organic also in their sense of growth adaptability and flexibility of use: technology and nature as one. So ideas of ‘Action Space Structure Combat Films’ were growing, the film connection came when Alan Nisbet agreed to join forces in a fortuitous moment when he walked through Bubble City.

Later in the development of Action Space, as it was finally called, ideas were cementing themselves more firmly, but still experimentally wedded to advancing our ideas to some future goal: later highlighted in our headed notepaper; ‘A Voluntary Association of Artists working in and between the areas of Play, Education and the Arts’.

Other influences at that time were direct experiences of performance from Better Books Basement of The People Show in Charing Cross Road, the Happenings of Allan Kaprow , one time painter and cartoonist, the American painters in their Happenings and Black Mountain College that included John Cage, Buckminster Fuller, (great domes! Instant structures!), Walter Gropious and Merce Cunningham: also the Russian revolutionary arts of 1917-1921 in their attempt to bring ‘universal abstraction’ in Modern Art to the people. Kandibnsky, Tatlin, Malevich, Lissitzky and the many set designs for the Kamerny Theatre, Moscow that include Meyerhold, Vesnin and Yaculov and the music of Pokofiev. (ref. Camilla Gray). A heady mix of information and inspiration, that became grist to the mill of our minds in looking into the future. Even the kinetic art of this time in the Kinetic Art Magazine 1966 published by Motion Books, a description of Schöffer’s work, where machines spin and whirr as large scale public art spectacles. As the critic M. Habasque pointed out in his essay, “From Space to Time”; “Schöffer no longer aspires to become integrated in the limited circuit of museums or collectors….but to become an object of daily use within the reach of all” (photo from Kinetic Art Mag).

I think too, the meetings in the banana warehouse in the old vegetable market of Covent Garden in the late 50’s with speakers like Kenneth Tynan, Christopher Logue, Lindsay Anderson, Ralph Samuel the chief instigator and convener and Stuart Hall, the sociologist, of the Universities and New Left Review, who organised these events, that were to me radical and mind bending. The Partisan Coffee House in Soho, London was also one of their projects and Mary and I curated exhibitions there. One was on political satire. Harold Wilson offered me a cigarette at the opening, “No thanks, I smoke roll-ups”. At that time we visited John Berger and Peter de Francia at their house in Hampsead. I had met John in 1955, when he was instrumental in arranging my exhibition at Helen Lessore’s Beaux Arts gallery. “Ah! Here come the Artisans” was always the greeting from Peter when we entered his Hampstead studio: such was his partisan manner! Though this was not really out of place as we ran a bespoke framing workshop at the time linked to the Artists International Association with its members as the main clients.

The New Left Review was founded in 1960, from a merger between the Boards of Universities and Left Review and The New Reasoner—two journals that had emerged out of the political repercussions of Suez and Hungary in 1956, reflecting respective rejections of the dominant 'revisionist' orthodoxy within the Labour Party and of the legacy of Stalinism in the Communist Party of Great Britain. I felt even at that time that things were beginning to move into expanding the consciousness of at least the intellectual milieus of professionals and students when it came to viewing the need for cultural change. Not forgetting of course in 1956, the ‘Angry Young Man’ of Osborn’s, the Establishment Club and much more in the excited trembling atmosphere of the time before the arrival of the swinging sixties. An interesting quote from myself from an interview in “Theoria to Theory”: a Cambridge University publication of 1970:

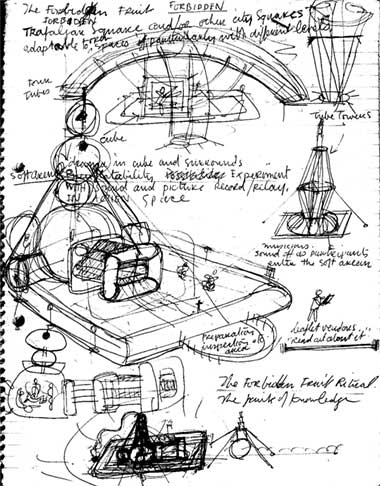

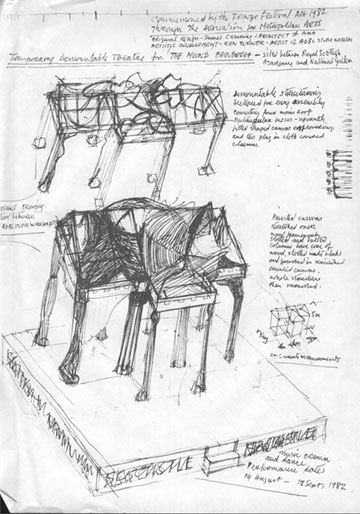

“We could only see that parts were beginning to fit together in a new way: we had to feel intuitively that things were right; there’s no grand master plan to work to. It often happens by accident or force of circumstance, which I think is sometimes exactly that, accidental”. John Willet, the authority on Brecht, whom we met through Berger also wrote in this issue, was later to become one of our Trustees. A.S. Neill, the free school pioneer who founded Summerhill in Suffolk, agreed to being our Patron at around the same time. Somehow things were building up but we had no idea what might come to fruition as new art, though we knew something or other was possible, it had to be, and by the time of the quote above it had become near to being a possibility. The only way to go forward was to match theory with action as immediately as we could, a kind of action research, as it were. From this time on in 1968’s “Bubble City”, when the Garden was in its full 600 square feet of operation, with music and performance and public engagement, a loftier idea as indicated in the above remarks, was forming in my mind. The demountable nature of the structure with its wooden pyramidal uprights and collapsible benches, supporting an inflatable ceiling was strong and functional enough to be suggesting working towards a greater and larger structure that was entirely inflated, instantly and anywhere, in both urban and countryside environments. This would be made possible by the development of new flexible sheet plastics re-enforced with nylon net and blown up by powerful centrifugal blowers, the Garden, incidentally, had used vacuum cleaners! My research into ‘plastics’ was proving itself with the use of re-enforced Polyvinyl Acetate in flexible sheet (Underlay of drawing and chemical structure of plastics, also geometric drawing of air structures) becoming a boon to environmental artists and performers in public spaces throughout the UK. Maurice Agis and Peter Jones were also practitioners and researchers in this art form, Jeff Shaw, and Graham Stevens, architects, were all also active in new ways of being artists/architects of the future.

Back in Bubble City, Bruce Lacey brought his large Humanoid, the public sliding down into its gory innards, a product emerging from his successful show at Bond Street’s Marlborough Gallery, a gallery that sponsored, in a small way, our next big project creative play three week residency (1969) in Wapping along with the Arts Council and Tower hamlets Council. By this time, fully fledged as Action Space, in our minds at least, encouraged by our efforts under Joan Littlewood, we were daring to go into what was to become a skinhead dominated local community. I don’t think we were starry eyed, but we didn’t realize the dangers and risks we were going to encounter as left wing art based adventurers. In the meantime we experienced the ‘instant structure’ ideas like ‘Pavilions in the Park’ initiated by Sue Braden, and ideas of ‘new activities’ becoming synonymous with artists working in the public realm, in an instant, with theatrical enactments wherever possible. ( see photos). Jeffery Shaw was most certainly an inspiration; an awesome air structure in ‘Bubble City’ of an inflatable dome with an undulating floor, was exceptionally spectacular. I also took part in a BBC Third Programme broadcast with Maurice Agis who took inspiration from Van Doesberg. Andrew Forge questioned us on what we saw as new in art. Maurice responded with explaining the ideas of the de Stijl movement and its far-reaching vision of colour and movement in architectural schemes that could be further developed. It is such a tragedy that the colour oriented air structures that he so believed in, and were so successful in their aim, has recently suffered this awful accident, when to my knowledge he is an efficient technical artist and cared very much about the objective placing of his work in the community. In the Broadcast of 1968 I stated that art could function to good effect if inflatable air structures were placed for public participation at strategic points in all built environments. In the sense of social responsibility, we were considered to have taken on the persona of gipsies in relation to the art world, I often referred to this description of myself because I did feel a different kind of artist, notwithstanding my being in a position of risk to a normal artistic career. To this day until the accident, Maurice was continuing with this sentiment of mine about public participation. I stopped in 1978 to return to painting as a means to renew my source of inspiration, performance and ideas on where to go next, as indeed I felt strongly that I had to continue to move forward in continuing the development of my own philosophy and practice in questioning the role of the artist in a different form: more on this turn of events later.

It is important to stress that at that time it was necessary to practically demonstrate ideas as they came out of intuitional feelings in order to prove something. This eventually led to the Arts Council and its “New Activities Panel” to finally accept what we were doing and concurrently to the award of grants to support our efforts to reach a wider public, Camden also responded with grants, in fact they were the first to do so. Eventually the Arts Council grant, interestingly enough, came from the Visual Arts Panel, presumably because of the visual effect of Air Structures. ‘New Activities’ was the title of an Arts Council publication by Frank Kermode with photos of Action Space’s air structures along with other artists working towards the concept of artists expanding the practicalities, both technically and artistically, of there being an art form that was particularly concerned with developing a wider public engagement within the arts.

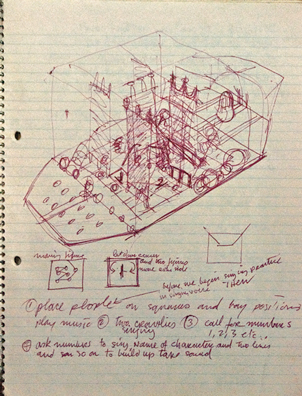

The Action Space that we developed was a programme to initiate the practice of performance, music and dance in order to bring a sense of drama into large scale structured environmental events. These disciplines were integrated into the physicality of the structures as stories and narratives, woven as if into the membrane of surfaces and the structural function of air as it pulsated, alive and breathing and circulating throughout the heaving sculptural body. (photos) Thus in themselves, the drama intensified the atmosphere and mood of the instant built/blown environment of the air structures. We as artists and operators took on roles or characters to play out dramas that nowadays are named as Durational Performance Art. Almost an accidental development because we had need of a defence mechanism, a kind of ‘accident’ in art to defend ourselves working with air structures and defence of the structures themselves. Because they were vulnerable to knife attacks we had to become characters larger than life as a form of security. We were I think, in 1969, a pointer to the practice of Performance Art of the 80’s. Action Space archives, which are quite extensive in film, photos and reports, exist as evidence of this practice. (see photos)

Thus many new techniques in construction and performance were in progress and we survived through sheer determination, and a conviction that our pioneering purpose was the right one, perhaps against all odds, and certainly at odds with the art world. A main feature in our development was that artists were paid to work for themselves and each other. That means, artist led, as self-employment was one of our objectives. Though wages were not large, (three pounds a week with grants for development). We were at least self employed as artists and enjoyed the risks involved as we strove to put forward ideas that were extremely suspect, of being concerned with an art form that ventured into new territories and strategies of social engagement in the Arts. Squatting in housing terms was really helpful for Action Space workers, as was the dole. We were nutters or weirdoes, as the Wapping kids used to call us, principally because we not only worked for nothing at that time, but also dressed peculiarly? I always had blue suede shoes on and stripped trousers, which protected me somewhat. Elvis to the rescue, unintentionally! Most of the artists grew their hair long and wore flared trousers, perhaps not looking as smart as the skin-heads, so in a sense, we separated ourselves almost without thinking. But was that a good thing? We were to find out. In present day thinking it is now considered that social engagement is what needs to be done and should be done, even though in my own thoughts and upon reflection it has become over institutionalized, primarily because as socially based art now is taking second place, losing its protest and real spirit of newness as a frontier-like action of protest springing from the visual art; losing that sense of fighting with ones back to the wall of the accepted parameters of art. That year in 1969, the graveyard with its surrounding high wall in Wapping, shutting out as it did the docks, as a one time thriving and bustling industry, was to become a metaphor, bringing to it a vivid meaning of the gap between art and life. An interesting link unfolds here from Kandinsky’s Universality of Art to Kaplan’s idea of the Blurring of Life and Art. The truth was actually there, in the metaphor of the wall. As an image (photo of wall), it was only too real as we battled our way in art and life far from the comfort and quiet of the West End Galleries: in their intellectual haven of theory, painting and the money it represented. I remember a ditty I wrote in the late 50’s as I strolled down Bond Street one day, observing the faster walking public, who I imagined were saying: “Can’t stop now mate, making money at a filthy rate”.

In my notebook of 1967 I wrote: “Space and scale to my mind were to become formal elements in direct relationship with the human scale, time and movement. Space works itself on people, and I personally like the feeling, as an artist, of working with large-scale spaces. My intention is either to fill such space in relation to architecture or into the form of landscape gardens, demountable/inflatable constructions of flexible plastic air constructions to be in themselves an environmental art form with public participation as its life force”

Before leaving this section, a fitting quote from Cedric Price. In indicating his radical approach to a people’s participation architecture, spoke about activities that were to be available in his future structures. “Choose what you want to do - or watch someone else doing it. Learn how to handle tools, paint, babies, machinery, or just listen to your favourite tune. Dance, talk or be lifted up to where you can see how other people make things work. Sit out over space with a drink or beginning a painting – or just lie back and stare at the sky”

Next, I will describe what happened in Wapping 1969, Action Space’s first real project. Maybe we could achieve some of the above quote from Cedric Price. I think we believed that this could be an objective. WAPPING LONDON E1 - 1969 and 1970 - A TWO WEEK RESIDENCY On the occasion of two consecutive summers Wapping, a run down area, untouched by development well into the 1980’s, was surrounded by docks, later to be filled in by the London Docklands Development Board, could be approached by a bridge from the Highway. The other entrance was from the east over another bridge; bridges that fed into the docks with the Thames running along one side. For Action Space it was like an island ignored by the Greater London Council with an odour of cinnamon and other spices coming from the warehouses, some still functioning, trading in paper and other goods. But the docks themselves were like wastewater, untouched, idle and unused. The weather though, surprisingly, was always bright and sunny. Was it the presence of the river, we wondered? It seemed so cut off and strange. I think we were surprised that English was even spoken.

Our first residence was in the Vicarage. On the first night we lay in our beds in almost a fearful state, because from the local pub nearby strong very loud menacing voices were singing over and over again, “Bye-bye Blackbird” well into the night. The next day, a Sunday, we met some of the singers who asked why we hadn’t come to join them: they were friendly, much to our relief! But we were yet to see how friendly or not the kids of Wapping were to our, as it were, invasion of their territory.

The design of Wapping Gardens wasn’t anything to shout about, but we managed to find a large enough space to begin. Our structures of wooden benches and pyramidal uprights from “Bubble City”, now funded by a £300 grant from the Arts Council enabled me to expand on the design to form an arena for action. A lot of kids and mothers turned up, we had advertised ourselves to the immediate community; they were expectant of something strange happening. (photos). Alan Nisbet, of Combat Films, was taking the photos.

We had some understanding that a dramatic beginning was necessary. Roddy Maud-Roxby, an actor from The Drama Machine, entered the Gardens at a dramatic distance from where we all were, approaching very slowly with masked face, taking the kids by surprise; Roddy had an immense sense of that real dramatic quality of presence; the mask added just that amount of mystery in the clear still morning. From then on it seemed that their attention was caught, and we starting devising many ways of creatively engaging them in theatre games and creative actions and painting. Thankfully our research into drama and theatre worked to some good effect, and Anne Martin, a lecturer and painter, from the Central School, where I was also teaching, set up a painting section that through the days ahead proved a haven for expression about the activity and experience of those taking part, most often with remarkable images relating to the spirit of the days events.

Unfortunately perhaps, in responding to our alternative notion of our sense of order as artists, the kids sometimes were seen to run amok into bushes and flowerbeds and maybe churn up the grass a little. Our thoughts at the time were, I think, on how free schools conduct discipline. My own presence was expressed through the use of a loudhailer as a means of control that I thought necessary. Later I was to discover a different voice projection by realizing that my voice was loud enough without artificial aid. It was also more human. This discovery was actually my first step into performance. The voice of command probably learnt from the parade ground of the Air Cadets when I was seventeen, perhaps fortuitously for me now aged forty-three. found a more appropriate area of action, but moderated dramatically, as the occasion demanded.

The next day the park keepers had had enough, looking at the state of the garden, and suggested that we move over to the Graveyard (photo) in the next street. This proved providential because we now had what we could claim as our very own territory and were free to enter into furthering our ideas as artists working with a community without obstruction from any quarter. Thus enabling us to focus on the practical research programme of art and play coming together in one environment over the days ahead. It almost seemed a perfect setting in which to carry through a fully prepared two-week programme of action with support from a variety of artists and performers coming in on a daily basis.

So there we were, in the graveyard, all ready to go. We had no idea that this was the beginning of a ten-year period leading us to the Drill Hall in Chenies Street, London W1, as our final base of operations from 1975 to 1978, with a client based revenue Arts Council Grant. At this moment however, in the summer 1968, we were faced with what could be described as our initiation into street and park based art/play events with a full-on, face-to-face encounter with a local community.

The mothers came to see what we would be providing for their kids, who were aged 4 to something like 16-17, and I guess where expecting a familiar play scheme set up, but they might have had a clue about it being different because we had advertised our coming as artists. The older youths to some extent thought it advisable to stay to one side, until we presented more dangerous things to do. The dangerous events were bouncing off half inflated ‘air beds’, or testing what height they could bounce. The air- beds, or cushions as they called them, were in constant use and often were seen being carried out of the graveyard, stealthily being moved down the street, as though we couldn’t see these brightly coloured objects. To my surprise they could be stopped by my loud commanding voice, just like that, amazing! Again my thoughts pondered on why an artist thought this was a necessary function, but later realizing this was a self imposed training. Coming out of events as they came into being, it was as if training was now inevitably bound up with the project experience; eventually recognizing its purpose and place in our development of how to proceed with performance. A sense of something real and a sense of excitement in ‘pioneering’ an unknown territory of performance: new, real and practical, there could be no stopping, despite the surprises in store or the dangers ahead, or the learning we had to do.

Street theatre such as Agiprop and Red Ladder were mentors that we looked to for techniques and methodology. The People Show, seen at Charing Cross Road’s in the depths of Better Books Basement, with the audience locked into cages, most decidedly always an inspiration. Then Lo and Behold, there they were, in our very own Graveyard. Mark Long, John Darling and Roland Miller making a dramatic entrance into the graveyard. One of them, with shouts and strange noises emerged from the derelict church across the road pulling a strong and very long rope. After much more noise and progress of the first figure moved slowly, luodly protesting, into the graveyard, the end of the rope came into view with another performer bound up in the rope. Pulling and tugging, shouting and cursing, the performers created a dramatic tension with the increasing tensioning of the rope. Their voices dominating the space; like something out of the white slave trade, the whole environment being, as it were, subjected to this totally unexpected powerful and cruel image: froze. Perhaps there were echoes of another age brought about by such a dramatically presented image. The whole graveyard and streets around with its normal human inhabitants, were as if rooted to the ground and transfixed, wrenched out of the everyday. Whatever anyone else thought, my impression was one of admiration, and another lesson learnt.

Much later around 1974, an equal effect on me was the Round House performance of ‘Frankenstein’ by Living Theatre. Julian Beck and Judith Malina from Brazil had formed this group, surprisingly in 1947. The 60’s being its wandering period of its exile from Brazil for political reasons: a wandering as a means to express ‘the relation of the artist to the struggle of the people’. I will quote the first lines in Julian’s book entitled ‘The Life of the Theatre’ published in1972.

“There is misery of the body and misery of the mind, and if the stars, whenever we looked at them, poured nectar into our mouths, and the grass became bread, we would still be sad. We live in a system that manufactures sorrow, spilling it out of its mill, the waters of sorrow, ocean, storm, and we drown, dead too soon.” He goes on to say, “I am a slave who came out of Egypt. I have a slave mentality. Out of the house of bondage, into the house of employment”.

Was Mark Long spilling out in sorrow in his bondage, or is that too simple?

The People Show Event in its successful development proved a good harbinger to effect other artists as they acted out their contributions in the ‘graveyard project.’ However before describing these I need to say something about the older boys of 16 plus who witnessed the event. The eventual progress of our programme having I think, some bearing on how they perceived The People Show’s performance. I need to say this because of the ethos of the times in which this was taking place. As indicated in my first recollection previously, in ideas and images, the feeling of rebellion against the order of the establishment was very evident and particularly amongst the young, in universities and art schools in this country and elsewhere in Europe. It was also evidenced in the papers such as International Times and the magazine OZ co-edited by Richard Neville and Jim Anderson (photo cover 1st edition) described as a “magazine of dissent’. Richard went back to Australia to become a successful author and is involved in a film to be released in 2009 entitled ‘Hippy, Hippy, Shake’.

In this context then, finding these young adults of 16-17 culturally and politically within our programme, it was the People Show that most probably propelled them into very quickly taking on a cultural change of their own. The spread of the ‘Skin-Head’ era was gaining momentum elsewhere in London, and it reached Wapping just in time for them to engineer for themselves a different look. A new sense of power was achieved as they consciously adopted this new grouping, visually identifiable by the difference in their clothing: crew cut hair, braces, shortened pants, steel capped bother boots as their uniform, and we had ours, casual, laid back; thus a distinctive difference, vividly visual. However we soon realized that this new grouping of identity was only able to perform as a group. Resonant of a kind of institutionalizing themselves as a group, we soon saw that they were not being able to function as individuals. One such time was when I was confronted with a line of skinheads who were determined to rock my car. Once they had my attention they stopped to see what I would do. In a moment of certainty I bellowed, “rock my car, any one of you, once more, and you wont know what’s hit you”. For a moment I waited in expectance of a violent response, but instead one of them winked and they dispersed. It was probably because I had singled them out as individuals that they were unable to re-act violently. This was really fortuitous, because my words weren’t really thought through at the time and I seemed unaware of the dangerous situation! Is this what artists should be doing? Not surprisingly perhaps it added to my standing, my kudos, as it were, a quality that was going to stand me in good stead later. I can’t help but ‘humorously out of context’ quote Socrates from my notebook of 1965. “We are spectators of a restless barbaric activity and whirl, which calls itself ‘the present’. Anxious, yet not despairing, we stand apart for a brief space, like spectators who are permitted to be witnesses of these tremendous struggles and transitions, Alas! It is the magic effect of these struggles that he who beholds them must also participate in them”.

Jeff Nutall, that iconoclastic adventurer of the arts and perpetrator of the publication, ‘Bomb Culture’, came into Wapping Graveyard as a human punch bag! Wrapped in foam, a moving spectacle for rolling, hitting and kicking. He must have done some research on Wapping’s nature of human behaviour. And it worked. It seemed that he ‘performed’ for hours, until his ‘audience’ realizing the impossibility of damaging the ‘object’ relented in their attacks. Offering himself as a target was a way to engage an audience. He had the active response, became as one of them, participating in the sport, they not realizing that it was an experimental art form they were pummelling. How could the audience know this? Would it make any difference if they did? The big question is, does art change anything in society? Does it have this capability? Has it ever? Jeff was a poet, social commentator, theatrical innovator, founder of the Peoples Show and jazz musician and with his book on counter culture is, or might be seen as an example for people to think more on the need to culturally challenge things. Michael Horovitze, poet, paid tribute to Jeff’s contribution to life thus:

“……..Because he was such a Blakean good mate to ‘Everything that lives is holy’, so exemplary an engineer of unfettered spontaneity”.

The Graveyard now under full swing hosted a great variety of artists and performers.

Ivor Cutler told stories and seemed hold the attention of kids extraordinary well. Ivor was actually teaching at the freeschool at Summerfield at the time, the head there eventually becoming the Patron of Action Space: that was .

Ed Berman with Interaction brought his troupe of players dramatically into the graveyard and interacted with a space/time odyssey to great absorption by the kids involved.

AMM the experimental music group under Cornelious Cardew brought violins that they didn’t mind being smashed to pieces. To them it was an unusual musical event with smashing sounds.

Ann Martin, painter with workshops and outdoor studio practice in painting all through each day.

Paula Saul with physical movement relating to the inflatables. The People show making their entrance dramatically.

Allan Nisbet with stories and dramatic events including building structures of wood environmentally.

Before going into how this project actually worked I want quickly to move to the present (May 2011) and quote Adam Curtis - film maker. as reported by Kathrine Viner in the Guardian.

Why don't we have big ideas or dreams any more? "Because now that there's nothing more important than you, how can you ever lose yourself in a grander idea? We're frightened of eccentricity, of loneliness. Individualism just wants to keep the machine stable, leads to a static world and a powerless world. Rand is individualism carried to its most extreme form, yet she's very popular, and not that far away from how a lot of people, especially the young, feel today."

All of this, Curtis says, means we're missing the bigger picture. "We never talk about power these days. We think we live in a non-hierarchical world, and we pretend not to be elitist now – which is, of course, an emotionally attractive idea, but it's just not true. And that's dangerous."

He believes that because British politics is now obliged to appear non-hierarchical, it has become managerialist, obsessed with process over vision – a recognisable idea to anyone who lives in this triangulated, professionalised political age. He says this doesn't just affect the political parties (although he singles out Andrew Lansley as managerialist-in-chief), but politics in its widest sense. "Even the 'march against the cuts'," he says, referring to the TUC march in London in March, "it was a noble thing, but it was still a managerial approach. We mustn't cut this, we can't cut that. Not, 'There is another way.' Why are we so frightened of a few bond managers? Why can't we challenge the 'markets'? Why do we treat them as if they're their own precious ecosystem? The idea of proper change, or really shifting things, is alien to us today. We just argue about how to manage a system best. It's a moment of high decadence. And we've forgotten that we do have deep responsibilities to people who really are powerless." (He has fascinating material on this about the west's interventions in Congo, as "a place that generates different kinds of myths about us as human beings, things that the west longs for but that also make us terrified".

I find this appropriate to how things developed after the years of Action Space and its inherent forcast that I will eventually go into in greater detail as the historical process evolves.

This story is now being told in its entirety in a book entitled:

Crashing Culture - an artists story from the 60s to the presnt day

Soon to be published, and hopefully will be linked to Huw Wahl's film on Action Space and contemporary thought on the democracy of culture.

The book is relevant to pedagogy and how the arts could function if the world moved towards an equality in the arts and culture. The argument in the book pursues a new paradigm, particularly for performance artists. That is, to bring the non-professional into the process of making art in collaboration with professionals. This is described in great detail in method and application on an existing project for 2015 and beyond.

below is a selection of paintings

4 x 4 to 5x5 feet - oil on canvas

from 1960 to 1988

PVC architecturual constructions for performance spaces 1965